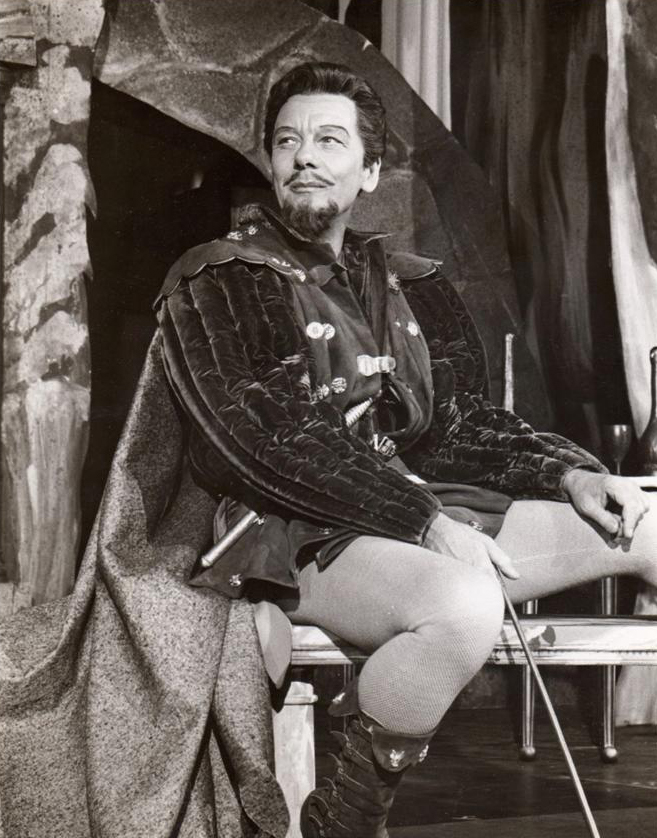

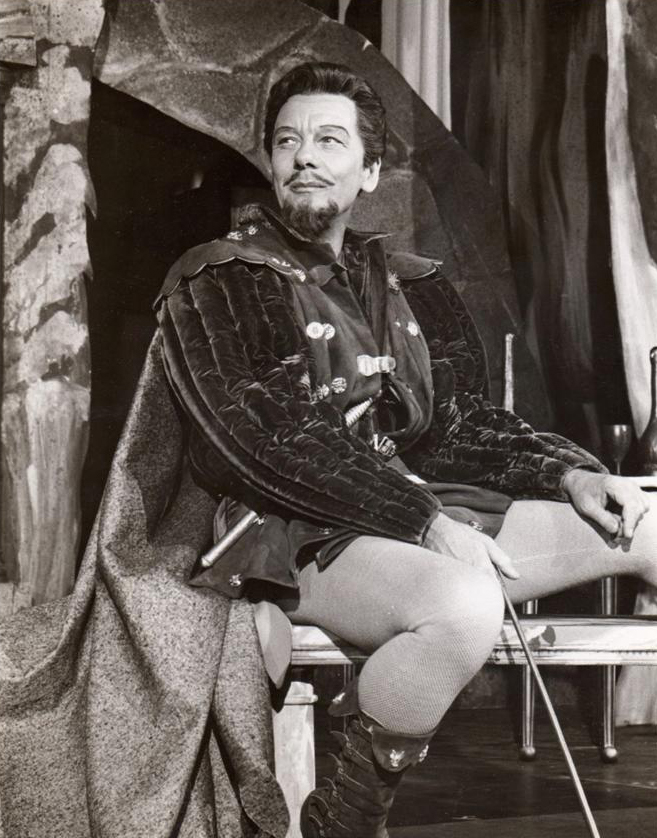

John Gielgud on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Arthur John Gielgud, (; 14 April 1904 – 21 May 2000) was an English actor and theatre director whose career spanned eight decades. With

Sir Arthur John Gielgud, (; 14 April 1904 – 21 May 2000) was an English actor and theatre director whose career spanned eight decades. With

radio drama; his younger sister Eleanor became John's secretary for many years.Morley, Sheridan and Robert Sharp

"Gielgud, Sir (Arthur) John (1904–2000)"

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, online edition, January 2011, retrieved 2 February 2014 On his father's side, Gielgud was of Lithuanian and Polish descent. The surname derives from

In May 1925 the Oxford production of ''The Cherry Orchard'' was brought to the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith. Gielgud again played Trofimov. His distinctive speaking voice attracted attention and led to work for

In May 1925 the Oxford production of ''The Cherry Orchard'' was brought to the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith. Gielgud again played Trofimov. His distinctive speaking voice attracted attention and led to work for

"Dean, Basil Herbert (1888–1978)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, online edition, January 2011, retrieved 12 August 2014 Intimidated, Gielgud accepted the position of understudy, with a guarantee that he would take over the lead from Coward when the latter, who disliked playing in long runs, left. In the event Coward, who had been overworking, suffered a nervous collapse three weeks after the opening night, and Gielgud played the lead for the rest of the run. The play ran for nearly a year in London and then went on tour. By this time Gielgud was earning enough to leave the family home and take a small flat in the West End. He had his first serious romantic relationship, living with John Perry, an unsuccessful actor, later a writer, who remained a lifelong friend after their affair ended. Morley makes the point that, like Coward, Gielgud's principal passion was the stage; both men had casual dalliances, but were more comfortable with "low-maintenance" long-term partners who did not impede their theatrical work and ambitions. In 1928 Gielgud made his

During his first season at the Old Vic, Gielgud played Romeo to the Juliet of

During his first season at the Old Vic, Gielgud played Romeo to the Juliet of

In 1932 Gielgud turned to directing. At the invitation of

In 1932 Gielgud turned to directing. At the invitation of  In May 1936 Gielgud played Trigorin in ''The Seagull'', with Evans as Arkadina and Ashcroft as Nina. Komisarjevsky directed, which made rehearsals difficult as Ashcroft, with whom he had been living, had just left him. Nonetheless, Morley writes, the critical reception was ecstatic. In the same year Gielgud made his last pre-war film, co-starring with

In May 1936 Gielgud played Trigorin in ''The Seagull'', with Evans as Arkadina and Ashcroft as Nina. Komisarjevsky directed, which made rehearsals difficult as Ashcroft, with whom he had been living, had just left him. Nonetheless, Morley writes, the critical reception was ecstatic. In the same year Gielgud made his last pre-war film, co-starring with

After his return from America in February 1937 Gielgud starred in ''He Was Born Gay'' by

After his return from America in February 1937 Gielgud starred in ''He Was Born Gay'' by

A 1944–45 season at the

A 1944–45 season at the

At the

At the  Returning to London later in 1953 Gielgud took over management of the Lyric, Hammersmith, for a classical season of ''Richard II'', Congreve's ''

Returning to London later in 1953 Gielgud took over management of the Lyric, Hammersmith, for a classical season of ''Richard II'', Congreve's '' During 1957 Gielgud directed Berlioz's ''

During 1957 Gielgud directed Berlioz's ''

During the early 1960s Gielgud had more successes as a director than as an actor. He directed the first London performance of

During the early 1960s Gielgud had more successes as a director than as an actor. He directed the first London performance of

In the first half of the decade Gielgud made seven films and six television dramas. Morley describes his choice as indiscriminate, but singles out for praise his performances in 1974 as the Old Cardinal in

In the first half of the decade Gielgud made seven films and six television dramas. Morley describes his choice as indiscriminate, but singles out for praise his performances in 1974 as the Old Cardinal in

''Who Was Who'', Oxford University Press, November 2012, retrieved 2 February 2014 From 1977 to 1989 Gielgud was president of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art – a symbolic position – and was the academy's first honorary fellow (1989). In 1996 the Globe Theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue was renamed the

"In Praise of the Holy Trinity: Olivier, Gielgud, Richardson"

, ''The New York Observer'', 12 January 1998; Gussow, Mel

, ''The New York Times'', 23 May 2000; and Beckett, Francis

"John Gielgud: Matinee Idol to Movie Star"

, ''The New Statesman'', 26 May 2011 The critic

"Obituary: Sir John Gielgud"

, ''The Independent'', 23 May 2000

John Gielgud , Stage , The Guardian

John Gielgud Archive

at the

Sir Arthur John Gielgud, (; 14 April 1904 – 21 May 2000) was an English actor and theatre director whose career spanned eight decades. With

Sir Arthur John Gielgud, (; 14 April 1904 – 21 May 2000) was an English actor and theatre director whose career spanned eight decades. With Ralph Richardson

Sir Ralph David Richardson (19 December 1902 – 10 October 1983) was an English actor who, with John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier, was one of the trinity of male actors who dominated the British stage for much of the 20th century. He wo ...

and Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the Theatre of the U ...

, he was one of the trinity of actors who dominated the British stage for much of the 20th century. A member of the Terry family

The Terry family was a British theatrical dynasty of the late 19th century and beyond. The family includes not only those members with the surname Terry, but also Neilsons, Craigs and Gielguds, to whom the Terrys were linked by marriage or blood ti ...

theatrical dynasty, he gained his first paid acting work as a junior member of his cousin Phyllis Neilson-Terry

Phyllis Neilson-Terry (15 October 1892 – 25 September 1977) was an English actress. She was a member of the third generation of the theatrical dynasty the Terry family. After early successes in the classics, including several leading Shakesp ...

's company in 1922. After studying at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA; ) is a drama school in London, England, that provides vocational conservatoire training for theatre, film, television, and radio. It is based in the Bloomsbury area of Central London, close to the Sen ...

he worked in repertory theatre

A repertory theatre is a theatre in which a resident company presents works from a specified repertoire, usually in alternation or rotation.

United Kingdom

Annie Horniman founded the first modern repertory theatre in Manchester after withdrawing ...

and in the West End before establishing himself at the Old Vic

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

*Old, Baranya, Hungary

* Old, Northamptonshire, England

*Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, Ma ...

as an exponent of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

in 1929–31.

During the 1930s Gielgud was a stage star in the West End and on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

, appearing in new works and classics. He began a parallel career as a director, and set up his own company at the Queen's Theatre, London. He was regarded by many as the finest Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

of his era, and was also known for high comedy roles such as John Worthing in ''The Importance of Being Earnest

''The Importance of Being Earnest, A Trivial Comedy for Serious People'' is a play by Oscar Wilde. First performed on 14 February 1895 at the St James's Theatre in London, it is a farcical comedy in which the protagonists maintain fictitious ...

''. In the 1950s Gielgud feared that his career was threatened when he was convicted and fined for a homosexual offence, but his colleagues and the public supported him loyally. When ' plays began to supersede traditional West End productions in the later 1950s he found no new suitable stage roles, and for several years he was best known in the theatre for his one-man Shakespeare show ''Ages of Man

The Ages of Man are the historical stages of human existence according to Greek mythology and its subsequent Roman interpretation.

Both Hesiod and Ovid offered accounts of the successive ages of humanity, which tend to progress from an origina ...

''. From the late 1960s he found new plays that suited him, by authors including Alan Bennett

Alan Bennett (born 9 May 1934) is an English actor, author, playwright and screenwriter. Over his distinguished entertainment career he has received numerous awards and honours including two BAFTA Awards, four Laurence Olivier Awards, and tw ...

, David Storey

David Malcolm Storey (13 July 1933 – 27 March 2017) was an English playwright, screenwriter, award-winning novelist and a professional rugby league player. He won the Booker Prize in 1976 for his novel ''Saville''. He also won the MacMillan ...

and Harold Pinter

Harold Pinter (; 10 October 1930 – 24 December 2008) was a British playwright, screenwriter, director and actor. A Nobel Prize winner, Pinter was one of the most influential modern British dramatists with a writing career that spanne ...

.

During the first half of his career, Gielgud did not take the cinema seriously. Though he made his first film in 1924, and had successes with ''The Good Companions

''The Good Companions'' is a novel by the English author J. B. Priestley.

Written in 1929, it follows the fortunes of a concert party on a tour of England. It is Priestley's most famous novel and established him as a national figure. It won ...

'' (1933) and ''Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

'' (1953), he did not begin a regular film career until his sixties. Gielgud appeared in more than sixty films between ''Becket

''Becket or The Honour of God'' (french: Becket ou l'honneur de Dieu) is a 1959 play written in French by Jean Anouilh. It is a depiction of the conflict between Thomas Becket and King Henry II of England leading to Becket's assassination in 117 ...

'' (1964), for which he received his first Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

nomination for playing Louis VII of France

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger, or the Young (french: link=no, le Jeune), was King of the Franks from 1137 to 1180. He was the son and successor of King Louis VI (hence the epithet "the Young") and married Duchess ...

, and ''Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

'' (1998). As the acid-tongued Hobson in ''Arthur

Arthur is a common male given name of Brittonic languages, Brythonic origin. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur. The etymology is disputed. It may derive from the Celtic ''Artos'' meaning “Bear”. An ...

'' (1981) he won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor

The Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor is an award presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). It is given in honor of an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance in a supporting role while worki ...

. His film work further earned him a Golden Globe Award

The Golden Globe Awards are accolades bestowed by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association beginning in January 1944, recognizing excellence in both American and international film and television. Beginning in 2022, there are 105 members of t ...

and two BAFTAs

The British Academy Film Awards, more commonly known as the BAFTA Film Awards is an annual award show hosted by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) to honour the best British and international contributions to film. The cere ...

.

Although largely indifferent to awards, Gielgud had the rare distinction of winning an Oscar, an Emmy, a Grammy, and a Tony. He was famous from the start of his career for his voice and his mastery of Shakespearean verse. He broadcast more than a hundred radio and television dramas between 1929 and 1994, and made commercial recordings of many plays, including ten of Shakespeare's. Among his honours, he was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

in 1953 and the Gielgud Theatre

The Gielgud Theatre is a West End theatre, located on Shaftesbury Avenue, at the corner of Rupert Street, in the City of Westminster, London. The house currently has 986 seats on three levels.

The theatre was designed by W. G. R. Sprague an ...

was named after him. From 1977 to 1989, he was president of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

Life and career

Background and early years

Gielgud was born on 14 April 1904 inSouth Kensington

South Kensington, nicknamed Little Paris, is a district just west of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with ...

, London, the third of the four children of Frank Henry Gielgud (1860–1949) and his second wife, Kate Terry-Gielgud, ''née'' Terry-Lewis (1868–1958). Gielgud's older brothers were Lewis

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* "Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...

, who became a senior official of the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

and UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

, and Val, later head of BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

..."Gielgud, Sir (Arthur) John (1904–2000)"

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, online edition, January 2011, retrieved 2 February 2014 On his father's side, Gielgud was of Lithuanian and Polish descent. The surname derives from

Gelgaudiškis

Gelgaudiškis () is a city in the Šakiai district municipality, Lithuania. It is located north of Šakiai. The city is just south of Neman River.

Name

Gelgaudiškis is the Lithuanian name of the city. Versions of the name in other language ...

, a village in Lithuania. The Counts Gielgud had owned the Gelgaudiškis Manor on the Nemunas

The Neman, Nioman, Nemunas or MemelTo bankside nations of the present: Lithuanian: be, Нёман, , ; russian: Неман, ''Neman''; past: ger, Memel (where touching Prussia only, otherwise Nieman); lv, Nemuna; et, Neemen; pl, Niemen; ...

river, but their estates were confiscated after they took part in a failed uprising against Russian rule in 1830–31. Jan Gielgud took refuge in England with his family;Croall (2011), pp. 8–9 one of his grandchildren was Frank Gielgud, whose maternal grandmother was a famous Polish actress, Aniela Aszpergerowa

Leontyna Aniela Aszpergerowa (29 November 1815 – 28 January 1902), known professionally as Aniela Aszpergerowa, was a Polish stage actress who achieved wide fame in Poland and in the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. She also took part in the ...

.Gielgud (1979), p. 22

Frank married into a family with wide theatrical connections. His wife, who was on the stage until she married, was the daughter of the actress Kate Terry

Kate Terry (21 April 1844 – 6 January 1924) was an English actress. The elder sister of the actress Ellen Terry, she was born into a theatrical family, made her debut when still a child, became a leading lady in her own right, and left the stag ...

, and a member of the stage dynasty that included Ellen

Ellen is a female given name, a diminutive of Elizabeth, Eleanor, Elena and Helen. Ellen was the 609th most popular name in the U.S. and the 17th in Sweden in 2004.

People named Ellen include:

* Ellen Adarna (born 1988), Filipino actress

* Elle ...

, Fred

Fred may refer to:

People

* Fred (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Mononym

* Fred (cartoonist) (1931–2013), pen name of Fred Othon Aristidès, French

* Fred (footballer, born 1949) (1949–2022), Frederico Ro ...

and Marion Terry

Marion Bessie Terry (born Mary Ann Bessy Terry; 13 October 1853 – 21 August 1930) was an English actress. In a career spanning half a century, she played leading roles in more than 125 plays. Always in the shadow of her older and more famous si ...

, Mabel Terry-Lewis

Mabel Gwynedd Terry-Lewis (born as Mabel Gwynedd Lewis) ( 28 October 1872 – 28 November 1957) was an English actress and a member of the Terry-Gielgud dynasty of actors of the 19th and 20th centuries.

After a successful career in her twe ...

and Edith

Edith is a feminine given name derived from the Old English words ēad, meaning 'riches or blessed', and is in common usage in this form in English, German, many Scandinavian languages and Dutch. Its French form is Édith. Contractions and vari ...

and Edward Gordon Craig

Edward Henry Gordon CraigSome sources give "Henry Edward Gordon Craig". (born Edward Godwin; 16 January 1872 – 29 July 1966), sometimes known as Gordon Craig, was an English modernist theatre practitioner; he worked as an actor, director and ...

.Gielgud (1979), pp. 222–223 Frank had no theatrical ambitions and worked all his life as a stockbroker in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

.

In 1912, aged eight, Gielgud went to Hillside preparatory school in Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

as his elder brothers had done. For a child with no interest in sport he acquitted himself reasonably well in cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

and rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

for the school. In class, he hated mathematics, was fair at classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

, and excelled at English and divinity

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.divine

. Hillside encouraged his interest in drama, and he played several leading roles in school productions, including Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autoc ...

in ''Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

'' and Shylock

Shylock is a fictional character in William Shakespeare's play ''The Merchant of Venice'' (c. 1600). A Venetian Jewish moneylender, Shylock is the play's principal antagonist. His defeat and conversion to Christianity form the climax of the ...

in ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

''.

After Hillside, Lewis and Val had won scholarships to Eton Eton most commonly refers to Eton College, a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England.

Eton may also refer to:

Places

*Eton, Berkshire, a town in Berkshire, England

* Eton, Georgia, a town in the United States

* Éton, a commune in the Meuse dep ...

and Rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

, respectively; lacking their academic achievement, John failed to secure such a scholarship. He was sent as a day boy to Westminster School

(God Gives the Increase)

, established = Earliest records date from the 14th century, refounded in 1560

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, head_label = Hea ...

where, as he later said, he had access to the West End "in time to touch the fringe of the great century of the theatre". He saw Sarah Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt (; born Henriette-Rosine Bernard; 22 or 23 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress who starred in some of the most popular French plays of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including '' La Dame Aux Camel ...

act, Adeline Genée dance and Albert Chevalier

Albert Chevalier (often listed as Albert Onésime Britannicus Gwathveoyd Louis Chevalier); (21 March 186110 July 1923), was an English music hall comedian, singer and musical theatre actor. He specialised in cockney related humour based on life ...

, Vesta Tilley

Matilda Alice Powles, Lady de Frece (13May 186416September 1952) was an English music hall performer. She adopted the stage name Vesta Tilley and became one of the best-known male impersonators of her era. Her career lasted from 1869 until 192 ...

and Marie Lloyd

Matilda Alice Victoria Wood (12 February 1870 – 7 October 1922), professionally known as Marie Lloyd (), was an English music hall singer, comedian and musical theatre actress. She was best known for her performances of songs such as " T ...

perform in the music hall

Music hall is a type of British theatrical entertainment that was popular from the early Victorian era, beginning around 1850. It faded away after 1918 as the halls rebranded their entertainment as variety. Perceptions of a distinction in Bri ...

s.Gielgud (2000), p. 36 The school choir sang in services at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, which appealed to his fondness for ritual. He showed talent at sketching, and for a while thought of scenic design

Scenic design (also known as scenography, stage design, or set design) is the creation of theatrical, as well as film or television scenery. Scenic designers come from a variety of artistic backgrounds, but in recent years, are mostly trained ...

as a possible career.

The young Gielgud's father took him to concerts, which he liked, and galleries and museums, "which bored me rigid". Both parents were keen theatregoers, but did not encourage their children to follow an acting career. Val Gielgud recalled, "Our parents looked distinctly sideways at the Stage as a means of livelihood, and when John showed some talent for drawing his father spoke crisply of the advantages of an architect's office." On leaving Westminster in 1921, Gielgud persuaded his reluctant parents to let him take drama lessons on the understanding that if he was not self-supporting by the age of twenty-five he would seek an office post.Gielgud (1979), p. 48

First acting experience

Gielgud, aged seventeen, joined a private drama school run by Constance Benson, wife of theactor-manager

An actor-manager is a leading actor who sets up their own permanent theatrical company and manages the business, sometimes taking over a theatre to perform select plays in which they usually star. It is a method of theatrical production used co ...

Sir Frank Benson. On the new boy's first day Lady Benson remarked on his physical awkwardness: "she said I walked like a cat with rickets

Rickets is a condition that results in weak or soft bones in children, and is caused by either dietary deficiency or genetic causes. Symptoms include bowed legs, stunted growth, bone pain, large forehead, and trouble sleeping. Complications may ...

. It dealt a severe blow to my conceit, which was a good thing." Before and after joining the school he played in several amateur productions, and in November 1921 made his debut with a professional company, though he himself was not paid. He played the Herald in ''Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (121 ...

'' at the Old Vic

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

*Old, Baranya, Hungary

* Old, Northamptonshire, England

*Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, Ma ...

; he had one line to speak and, he recalled, spoke it badly. He was kept on for the rest of the season in walk-on parts in ''King Lear

''King Lear'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare.

It is based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his power and land between two of his daughters. He becomes destitute and insane an ...

'', ''Wat Tyler'' and ''Peer Gynt

''Peer Gynt'' (, ) is a five- act play in verse by the Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen published in 1876. Written in Norwegian, it is one of the most widely performed Norwegian plays. Ibsen believed ''Per Gynt'', the Norwegian fairy tale on wh ...

'', with no lines.

Gielgud's first substantial engagement came through his family. In 1922 his cousin Phyllis Neilson-Terry

Phyllis Neilson-Terry (15 October 1892 – 25 September 1977) was an English actress. She was a member of the third generation of the theatrical dynasty the Terry family. After early successes in the classics, including several leading Shakesp ...

invited him to tour in J. B. Fagan's ''The Wheel'', as understudy

In theater, an understudy, referred to in opera as cover or covering, is a performer who learns the lines and blocking or choreography of a regular actor, actress, or other performer in a play. Should the regular actor or actress be unable to ap ...

, bit-part player and assistant stage manager, an invitation he accepted. A colleague, recognising that the young man had talent but lacked technique, recommended him to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA; ) is a drama school in London, England, that provides vocational conservatoire training for theatre, film, television, and radio. It is based in the Bloomsbury area of Central London, close to the Sen ...

(RADA). Gielgud was awarded a scholarship to the academy and trained there throughout 1923 under Kenneth Barnes, Helen Haye

Helen Haye (born Helen Hay, 28 August 1874 – 1 September 1957) was a British stage and film actress.

New York Times. 3 Septem ...

and New York Times. 3 Septem ...

Claude Rains

William Claude Rains (10 November 188930 May 1967) was a British actor whose career spanned almost seven decades. After his American film debut as Dr. Jack Griffin in ''The Invisible Man'' (1933), he appeared in such highly regarded films as '' ...

.

The actor-manager Nigel Playfair

Sir Nigel Ross Playfair (1 July 1874 – 19 August 1934) was an English actor and director, known particularly as actor-manager of the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, in the 1920s.

After acting as an amateur while practising as a lawyer, he turne ...

, a friend of Gielgud's family, saw him in a student presentation of J. M. Barrie's ''The Admirable Crichton

''The Admirable Crichton'' is a comic stage play written in 1902 by J. M. Barrie.

Origins

Barrie took the title from the sobriquet of a fellow Scot, the polymath James Crichton, a 16th-century genius and athlete. The epigram-loving Ernest is p ...

''. Playfair was impressed and cast him as Felix, the poet-butterfly, in the British premiere of the Čapek brothers' '' The Insect Play''. Gielgud later said that he made a poor impression in the part: "I am surprised that the audience did not throw things at me." The critics were cautious but not hostile to the play; it did not attract the public and closed after a month. While still continuing his studies at RADA, Gielgud appeared again for Playfair in ''RobertE Lee'' by John Drinkwater.Morley, p. 33 After leaving the academy at the end of 1923 Gielgud played a Christmas season as Charley in ''Charley's Aunt

''Charley's Aunt'' is a farce in three acts written by Brandon Thomas. The story centres on Lord Fancourt Babberley, an undergraduate whose friends Jack and Charley persuade him to impersonate the latter's aunt. The complications of the plot inc ...

'' in the West End, and then joined Fagan's repertory

A repertory theatre is a theatre in which a resident company presents works from a specified repertoire, usually in alternation or rotation.

United Kingdom

Annie Horniman founded the first modern repertory theatre in Manchester after withdrawing ...

company at the Oxford Playhouse

Oxford Playhouse is a theatre designed by Edward Maufe and F.G.M. Chancellor. It is situated in Beaumont Street, Oxford, opposite the Ashmolean Museum.

History

The Playhouse was founded as ''The Red Barn'' at 12 Woodstock Road, North Oxfor ...

.

Gielgud was in the Oxford company in January and February 1924, from October 1924 to the end of January 1925, and in August 1925.Croall (2000), pp. 534–545; Morley, pp. 459–477; and Tanitch, pp. 178–191 He played a wide range of parts in classics and modern plays, greatly increasing his technical abilities in the process. The role he most enjoyed was Trofimov in ''The Cherry Orchard

''The Cherry Orchard'' (russian: Вишнёвый сад, translit=Vishnyovyi sad) is the last play by Russian playwright Anton Chekhov. Written in 1903, it was first published by ''Znaniye'' (Book Two, 1904), and came out as a separate edition ...

'', his first experience of Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; 29 January 1860 Old Style date 17 January. – 15 July 1904 Old Style date 2 July.) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer who is considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career ...

: "It was the first time I ever went out on stage feeling that perhaps, after all, I could really be an actor."

Early West End roles

Between Gielgud's first two Oxford seasons, the producer Barry Jackson cast him asRomeo

Romeo Montague () is the male protagonist of William Shakespeare's tragedy ''Romeo and Juliet''. The son of Lord Montague and his wife, Lady Montague, he secretly loves and marries Juliet, a member of the rival House of Capulet, through a priest ...

to the Juliet

Juliet Capulet () is the female protagonist in William Shakespeare's romantic tragedy ''Romeo and Juliet''. A 13-year-old girl, Juliet is the only daughter of the patriarch of the House of Capulet. She falls in love with the male protagonist R ...

of Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies

Dame Gwen Lucy Ffrangcon-Davies, (25 January 1891 – 27 January 1992) was a British actress and centenarian.

Early life

She was born in London of a Welsh family; the name "Ffrangcon" is said to originate from a valley in Snowdonia. Her pare ...

at the Regent's Theatre, London, in May 1924. The production was not a great success, but the two performers became close friends and frequently worked together throughout their careers. Gielgud made his screen debut during 1924 as Daniel Arnault in Walter Summers

Walter Summers (1892–1973) was a British film director and screenwriter.

Biography

Born in Barnstaple to a family of actors, British motion picture director Walter Summers began his career in the family trade; his first contact with filmmaki ...

's silent film '' Who Is the Man?'' (1924).

In May 1925 the Oxford production of ''The Cherry Orchard'' was brought to the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith. Gielgud again played Trofimov. His distinctive speaking voice attracted attention and led to work for

In May 1925 the Oxford production of ''The Cherry Orchard'' was brought to the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith. Gielgud again played Trofimov. His distinctive speaking voice attracted attention and led to work for BBC Radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927). The service provides national radio stations covering th ...

, which his biographer Sheridan Morley

Sheridan Morley (5 December 1941 − 16 February 2007) was an English author, biographer, critic and broadcaster. He was the official biographer of Sir John Gielgud and wrote biographies of many other theatrical figures he had known, including ...

calls "a medium he made his own for seventy years". In the same year Noël Coward

Sir Noël Peirce Coward (16 December 189926 March 1973) was an English playwright, composer, director, actor, and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what ''Time'' magazine called "a sense of personal style, a combination of cheek and ...

chose Gielgud as his understudy in his play ''The Vortex

''The Vortex'' is a play in three acts by the English writer and actor Noël Coward. The play depicts the sexual vanity of a rich, ageing beauty, her troubled relationship with her adult son, and drug abuse in British society circles after the ...

''. For the last month of the West End run Gielgud took over Coward's role of Nicky Lancaster, the drug-addicted son of a nymphomaniac mother. It was in Gielgud's words "a highly-strung, nervous, hysterical part which depended a lot upon emotion".Gielgud (1979), p. 61 He found it tiring to play because he had not yet learned how to pace himself, but he thought it "a thrilling engagement because it led to so many great things afterwards".

The success of ''The Cherry Orchard'' led to what one critic called a "Chekhov boom" in British theatres, and Gielgud was among its leading players. As Konstantin in ''The Seagull

''The Seagull'' ( rus, Ча́йка, r=Cháyka, links=no) is a play by Russian dramatist Anton Chekhov, written in 1895 and first produced in 1896. ''The Seagull'' is generally considered to be the first of his four major plays. It dramatises t ...

'' in October 1925 he impressed the Russian director Theodore Komisarjevsky

Fyodor Fyodorovich Komissarzhevsky (russian: Фёдор Фёдорович Комиссаржевский; 23 May 1882 – 17 April 1954), or Theodore Komisarjevsky, was a Russian, later British, theatrical director and designer. He began his car ...

, who cast him as Tusenbach in the British premiere of '' Three Sisters''. The production received enthusiastic reviews, and Gielgud's highly praised performance enhanced his reputation as a potential star. There followed three years of mixed fortunes for him, with successes in fringe productions, but West End stardom was elusive.

In 1926 the producer Basil Dean

Basil Herbert Dean CBE (27 September 1888 – 22 April 1978) was an English actor, writer, producer and director in the theatre and in cinema. He founded the Liverpool Repertory Company in 1911 and in the First World War, after organising unoff ...

offered Gielgud the lead role, Lewis Dodd, in a dramatisation of Margaret Kennedy

Margaret Moore Kennedy (23 April 1896 – 31 July 1967) was an English novelist and playwright. Her most successful work, as a novel and as a play, was '' The Constant Nymph''. She was a productive writer and several of her works were filmed. T ...

's best-selling novel, '' The Constant Nymph''. Before rehearsals began Dean found that a bigger star than Gielgud was available, namely Coward, to whom he gave the part. Gielgud had an enforceable contractual claim to the role, but Dean, a notorious bully, was a powerful force in British theatre.Roose-Evans, James"Dean, Basil Herbert (1888–1978)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, online edition, January 2011, retrieved 12 August 2014 Intimidated, Gielgud accepted the position of understudy, with a guarantee that he would take over the lead from Coward when the latter, who disliked playing in long runs, left. In the event Coward, who had been overworking, suffered a nervous collapse three weeks after the opening night, and Gielgud played the lead for the rest of the run. The play ran for nearly a year in London and then went on tour. By this time Gielgud was earning enough to leave the family home and take a small flat in the West End. He had his first serious romantic relationship, living with John Perry, an unsuccessful actor, later a writer, who remained a lifelong friend after their affair ended. Morley makes the point that, like Coward, Gielgud's principal passion was the stage; both men had casual dalliances, but were more comfortable with "low-maintenance" long-term partners who did not impede their theatrical work and ambitions. In 1928 Gielgud made his

Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

debut as the Grand Duke Alexander in Alfred Neumann's ''The Patriot''. The play was a failure, closing after a week, but Gielgud liked New York and received favourable reviews from critics including Alexander Woollcott

Alexander Humphreys Woollcott (January 19, 1887 – January 23, 1943) was an American drama critic and commentator for ''The New Yorker'' magazine, a member of the Algonquin Round Table, an occasional actor and playwright, and a prominent radio p ...

and Brooks Atkinson

Justin Brooks Atkinson (November 28, 1894 – January 14, 1984) was an American theatre critic. He worked for ''The New York Times'' from 1922 to 1960. In his obituary, the ''Times'' called him "the theater's most influential reviewer of his ...

. After returning to London he starred in a succession of short runs, including Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright and theatre director. As one of the founders of modernism in theatre, Ibsen is often referred to as "the father of realism" and one of the most influential playw ...

's ''Ghosts

A ghost is the soul or spirit of a dead person or animal that is believed to be able to appear to the living. In ghostlore, descriptions of ghosts vary widely from an invisible presence to translucent or barely visible wispy shapes, to rea ...

'' with Mrs Patrick Campbell

Beatrice Rose Stella Tanner (9 February 1865 – 9 April 1940), better known by her stage name Mrs Patrick Campbell or Mrs Pat, was an English stage actress, best known for appearing in plays by Shakespeare, Shaw and Barrie. She also toured th ...

(1928), and Reginald Berkeley

Reginald Cheyne Berkeley (18 August 1890 – 30 March 1935) was a Liberal Party politician in the United Kingdom, and later a writer of stage plays, then a screenwriter in Hollywood. He had trained as a lawyer. He died in Los Angeles from pneumo ...

's ''The Lady with a Lamp'' (1929) with Edith Evans

Dame Edith Mary Evans, (8 February 1888 – 14 October 1976) was an English actress. She was best known for her work on the stage, but also appeared in films at the beginning and towards the end of her career. Between 1964 and 1968, she was no ...

and Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies. In 1928 he made his second film, '' The Clue of the New Pin''. This, billed as "the first British full-length talkie

A sound film is a motion picture

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, percep ...

", was an adaptation of an Edgar Wallace

Richard Horatio Edgar Wallace (1 April 1875 – 10 February 1932) was a British writer.

Born into poverty as an illegitimate London child, Wallace left school at the age of 12. He joined the army at age 21 and was a war correspondent during th ...

mystery story; Gielgud played a young scoundrel who commits two murders and very nearly a third before he himself is killed.

Old Vic

In 1929Harcourt Williams

Ernest George Harcourt Williams (30 March 1880 – 13 December 1957) was an English actor and director. After early experience in touring companies he established himself as a character actor and director in the West End. From 1929 to 1934 he ...

, newly appointed as director of productions at the Old Vic, invited Gielgud to join the company for the forthcoming season. The Old Vic, in an unfashionable area of London south of the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

, was run by Lilian Baylis

Lilian Mary Baylis

CH (9 May 187425 November 1937) was an English theatrical producer and manager. She managed the Old Vic and Sadler's Wells theatres in London and ran an opera company, which became the English National Opera (ENO); a theatre ...

to offer plays and operas to a mostly working-class audience at low ticket prices. She paid her performers very modest wages, but the theatre was known for its unrivalled repertory of classics, mostly Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, and Gielgud was not the first West End star to take a large pay cut to work there. It was, in Morley's words, the place to learn Shakespearean technique and try new ideas.

Adele Dixon

Adele Dixon (born Adela Helena Dixon; 3 June 1908 – 11 April 1992) was an English actress and singer. She sang at the start of regular broadcasts of the BBC Television Service on 2 November 1936.

After an early start as a child actress, an ...

, Antonio

Antonio is a masculine given name of Etruscan origin deriving from the root name Antonius. It is a common name among Romance language-speaking populations as well as the Balkans and Lusophone Africa. It has been among the top 400 most popular male ...

in ''The Merchant of Venice'', Cleante in '' The Imaginary Invalid'', the title role

The title character in a Narrative, narrative work is one who is named or referred to in the title of the work. In a performed work such as a play or film, the performer who plays the title character is said to have the title role of the piece. The ...

in ''Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father died ...

'', and Oberon

Oberon () is a king of the fairies in medieval and Renaissance literature. He is best known as a character in William Shakespeare's play ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'', in which he is King of the Fairies and spouse of Titania, Queen of the Fair ...

in ''A Midsummer Night's Dream

''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' is a comedy written by William Shakespeare 1595 or 1596. The play is set in Athens, and consists of several subplots that revolve around the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. One subplot involves a conflict amon ...

''. His Romeo was not well reviewed, but as Richard II Gielgud was recognised by critics as a Shakespearean actor of undoubted authority. The reviewer in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' commented on his sensitiveness, strength and firmness, and called his performance "work of genuine distinction, not only in its grasp of character, but in its control of language". Later in the season he was cast as Mark Antony in ''Julius Caesar'', Orlando

Orlando () is a city in the U.S. state of Florida and is the county seat of Orange County. In Central Florida, it is the center of the Orlando metropolitan area, which had a population of 2,509,831, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures rele ...

in ''As You Like It

''As You Like It'' is a pastoral comedy by William Shakespeare believed to have been written in 1599 and first published in the First Folio in 1623. The play's first performance is uncertain, though a performance at Wilton House in 1603 has b ...

'', the Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

in '' Androcles and the Lion'' and the title role in Pirandello's '' The Man with the Flower in His Mouth''.

In April 1930 Gielgud finished the season playing Hamlet. Williams's production used the complete text of the play. This was regarded as a radical innovation; extensive cuts had been customary for earlier productions. A running time of nearly five hours did not dampen the enthusiasm of the public, the critics or the acting profession. Sybil Thorndike

Dame Agnes Sybil Thorndike, Lady Casson (24 October 18829 June 1976) was an English actress whose stage career lasted from 1904 to 1969.

Trained in her youth as a concert pianist, Thorndike turned to the stage when a medical problem with her ...

said, "I never hoped to see Hamlet played as in one's dreams ... I've had an evening of being swept right off my feet into another life – far more real than the life I live in, and moved, moved beyond words." The production gained such a reputation that the Old Vic began to attract large numbers of West End theatregoers. Demand was so great that the cast moved to the Queen's Theatre, in Shaftesbury Avenue

Shaftesbury Avenue is a major road in the West End of London, named after The 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. It runs north-easterly from Piccadilly Circus to New Oxford Street, crossing Charing Cross Road at Cambridge Circus. From Piccadilly Cir ...

, where Williams staged the piece with the text discreetly shortened. The effect of the cuts was to give the title role even more prominence. Gielgud's Hamlet was richly praised by the critics. Ivor Brown

Ivor John Carnegie Brown CBE (25 April 1891 – 22 April 1974) was a British journalist and man of letters.

Biography

Born in Penang, Malaya, Brown was the younger of two sons of Dr. William Carnegie Brown, a specialist in tropical diseases, ...

called it "a tremendous performance ... the best Hamlet of yexperience". James Agate

James Evershed Agate (9 September 1877 – 6 June 1947) was an English diarist and theatre critic between the two world wars. He took up journalism in his late twenties and was on the staff of ''The Manchester Guardian'' in 1907–1914. He later ...

wrote, "I have no hesitation whatsoever in saying that it is the high water-mark of English Shakespearean acting of our time."

Hamlet was a role with which Gielgud was associated over the next decade and more. After the run at the Queen's finished he turned to another part for which he became well known, John Worthing in ''The Importance of Being Earnest

''The Importance of Being Earnest, A Trivial Comedy for Serious People'' is a play by Oscar Wilde. First performed on 14 February 1895 at the St James's Theatre in London, it is a farcical comedy in which the protagonists maintain fictitious ...

''. Gielgud's biographer Jonathan Croall comments that the two roles illustrated two sides of the actor's personality: on the one hand the romantic and soulful Hamlet, and on the other the witty and superficial Worthing. The formidable Lady Bracknell was played by his aunt, Mabel Terry-Lewis. ''The Times'' observed, "Mr Gielgud and Miss Terry-Lewis together are brilliant ... they have the supreme grace of always allowing Wilde

Wilde is a surname. Notable people with the name include:

In arts and entertainment In film, television, and theatre

* ''Wilde'' a 1997 biographical film about Oscar Wilde

* Andrew Wilde (actor), English actor

* Barbie Wilde (born 1960), Canadi ...

to speak in his own voice."

Returning to the Old Vic for the 1930–31 season, Gielgud found several changes to the company. Donald Wolfit

Sir Donald Wolfit, KBE (born Donald Woolfitt; Harwood, Ronald"Wolfit, Sir Donald (1902–1968)" ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, January 2008; accessed 14 July 2009 20 April 1902 ...

, who loathed him and was himself disliked by his colleagues, was dropped, as was Adele Dixon.Croall (2000), p. 134 Gielgud was uncertain of the suitability of the most prominent new recruit, Ralph Richardson

Sir Ralph David Richardson (19 December 1902 – 10 October 1983) was an English actor who, with John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier, was one of the trinity of male actors who dominated the British stage for much of the 20th century. He wo ...

, but Williams was sure that after this season Gielgud would move on; he saw Richardson as a potential replacement. The two actors had little in common. Richardson recalled, "He was a kind of brilliant butterfly, while I was a very gloomy sort of boy", and "I found his clothes extravagant, I found his conversation flippant. He was the New Young Man of his time and I didn't like him." The first production of the season was ''Henry IV, Part 1

''Henry IV, Part 1'' (often written as ''1 Henry IV'') is a history play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written no later than 1597. The play dramatises part of the reign of King Henry IV of England, beginning with the battle at ...

'', in which Gielgud as Hotspur had the best of the reviews. Richardson's notices, and the relationship of the two leading men, improved markedly when Gielgud, who was playing Prospero

Prospero ( ) is a fictional character and the protagonist of William Shakespeare's play '' The Tempest''.

Prospero is the rightful Duke of Milan, whose usurping brother, Antonio, had put him (with his three-year-old daughter, Miranda) to sea ...

in '' The Tempest'', helped Richardson with his performance as Caliban

Caliban ( ), son of the witch Sycorax, is an important character in William Shakespeare's play '' The Tempest''.

His character is one of the few Shakespearean figures to take on a life of its own "outside" Shakespeare's own work: as Russell H ...

:

The friendship and professional association lasted for more than fifty years, until the end of Richardson's life. Gielgud's other roles in this season were Lord Trinket in ''The Jealous Wife

''The Jealous Wife'' is a 1761 British play by George Colman the Elder. A comedy, it was first performed at the Drury Lane Theatre on 12 February 1761 and ran for 19 performances in its first season and 70 by the end of the century. It was trans ...

'', Richard II again, Antony in ''Antony and Cleopatra

''Antony and Cleopatra'' (First Folio title: ''The Tragedie of Anthonie, and Cleopatra'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. The play was first performed, by the King's Men, at either the Blackfriars Theatre or the Globe Theatre in around ...

'', Malvolio

Malvolio is a fictional character in William Shakespeare's comedy ''Twelfth Night, or What You Will''. His name means "ill will" in Italian, referencing his disagreeable nature. He is the vain, pompous, authoritarian steward of Olivia's househo ...

in ''Twelfth Night

''Twelfth Night'', or ''What You Will'' is a romantic comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written around 1601–1602 as a Twelfth Night's entertainment for the close of the Christmas season. The play centres on the twins Vio ...

'', Sergius in ''Arms and the Man

''Arms and the Man'' is a comedy by George Bernard Shaw, whose title comes from the opening words of Virgil's ''Aeneid'', in Latin:

''Arma virumque cano'' ("Of arms and the man I sing").

The play was first produced on 21 April 1894 at the Aven ...

'', Benedick in ''Much Ado About Nothing

''Much Ado About Nothing'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare thought to have been written in 1598 and 1599.See textual notes to ''Much Ado About Nothing'' in ''The Norton Shakespeare'' ( W. W. Norton & Company, 1997 ) p. 1387 The play ...

'' – another role for which he became celebrated – and he concluded the season as King Lear

''King Lear'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare.

It is based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his power and land between two of his daughters. He becomes destitute and insane an ...

. His performance divided opinion. ''The Times'' commented, "It is a mountain of a part, and at the end of the evening the peak remains unscaled"; in ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'', however, Brown wrote that Gielgud "is a match for the thunder, and at length takes the Dover road with a broken tranquillity that allowed every word of the King's agony to be clear as well as poignant".

West End star

Returning to the West End, Gielgud starred in J. B.Priestley's ''The Good Companions

''The Good Companions'' is a novel by the English author J. B. Priestley.

Written in 1929, it follows the fortunes of a concert party on a tour of England. It is Priestley's most famous novel and established him as a national figure. It won ...

'', adapted for the stage by the author and Edward Knoblock

Edward Knoblock (born Edward Gustavus Knoblauch; 7 April 1874 – 19 July 1945) was a playwright and novelist, originally American and later a naturalised British citizen. He wrote numerous plays, often at the rate of two or three a year, of whic ...

. The production ran from May 1931 for 331 performances, and Gielgud described it as his first real taste of commercial success. He played Inigo Jollifant, a young schoolmaster who abandons teaching to join a travelling theatre troupe. This crowd-pleaser drew disapproval from the more austere reviewers, who felt Gielgud should be doing something more demanding, but he found playing a conventional juvenile lead had challenges of its own and helped him improve his technique. During the run of the play he made another film, ''Insult

An insult is an expression or statement (or sometimes behavior) which is disrespectful or scornful. Insults may be intentional or accidental. An insult may be factual, but at the same time pejorative, such as the word "inbred".

Jocular exc ...

'' (1932), a melodrama

A modern melodrama is a dramatic work in which the plot, typically sensationalized and for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodramas typically concentrate on dialogue that is often bombastic or exces ...

about the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (french: Légion étrangère) is a corps of the French Army which comprises several specialties: infantry, Armoured Cavalry Arm, cavalry, Military engineering, engineers, Airborne forces, airborne troops. It was created ...

, and he starred in a cinema version of ''The Good Companions'' in 1933, with Jessie Matthews

Jessie Margaret Matthews (11 March 1907 – 19 August 1981) was an English actress, dancer and singer of the 1920s and 1930s, whose career continued into the post-war period.

After a string of hit stage musicals and films in the mid-1930s, Ma ...

. A letter to a friend reveals Gielgud's view of film acting: "There is talk of my doing Inigo in the film of ''The Good Companions'', which appals my soul but appeals to my pocket." In his first volume of memoirs, published in 1939, Gielgud devoted two pages to describing the things about filming that he detested. Unlike his contemporaries Richardson and Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the Theatre of the U ...

, he made few films until after the Second World War, and did not establish himself as a prominent film actor until many years after that. As he put it in 1994, "I was stupid enough to toss my head and stick to the stage while watching Larry and Ralph sign lucrative Korda contracts."

In 1932 Gielgud turned to directing. At the invitation of

In 1932 Gielgud turned to directing. At the invitation of George Devine

George Alexander Cassady Devine (20 November 1910 – 20 January 1966) was an English theatrical manager, director, teacher, and actor based in London from the early 1930s until his death. He also worked in TV and film.

Early life and education

...

, the president of the Oxford University Dramatic Society

The Oxford University Dramatic Society (OUDS) is the principal funding body and provider of theatrical services to the many independent student productions put on by students in Oxford, England. Not all student productions at Oxford University a ...

, Gielgud took charge of a production of ''Romeo and Juliet'' by the society, featuring two guest stars: Peggy Ashcroft

Dame Edith Margaret Emily Ashcroft (22 December 1907 – 14 June 1991), known professionally as Peggy Ashcroft, was an English actress whose career spanned more than 60 years.

Born to a comfortable middle-class family, Ashcroft was deter ...

as Juliet and Edith Evans as the Nurse. The rest of the cast were students, led by Christopher Hassall

Christopher Vernon Hassall (24 March 1912 – 25 April 1963) was an English actor, dramatist, librettist, lyricist and poet, who found his greatest fame in a memorable musical partnership with the actor and composer Ivor Novello after worki ...

as Romeo, and included Devine, William Devlin and Terence Rattigan

Sir Terence Mervyn Rattigan (10 June 191130 November 1977) was a British dramatist and screenwriter. He was one of England's most popular mid-20th-century dramatists. His plays are typically set in an upper-middle-class background.Geoffrey Wan ...

. The experience was satisfactory to Gielgud: he enjoyed the attentions of the undergraduates, had a brief affair with one of them, James Lees-Milne

(George) James Henry Lees-Milne (6 August 1908 – 28 December 1997) was an English writer and expert on country houses, who worked for the National Trust from 1936 to 1973. He was an architectural historian, novelist and biographer. His extensi ...

, and was widely praised for his inspiring direction and his protégés' success with the play. Already notorious for his innocent slips of the tongue (he called them "Gielgoofs"), in a speech after the final performance he referred to Ashcroft and Evans as "Two leading ladies, the like of whom I hope I shall never meet again".

During the rest of 1932 Gielgud played in a new piece, ''Musical Chairs'' by Ronald Mackenzie, and directed one new and one classic play, ''Strange Orchestra'' by Rodney Ackland

Rodney Ackland (18 May 1908 in Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex – 6 December 1991 in Richmond upon Thames, Surrey) was an English playwright, actor, theatre director and screenwriter.

Born as Norman Ackland Bernstein in Southend, Essex, to a Jewish fat ...

in the West End, and ''The Merchant of Venice'' at the Old Vic, with Malcolm Keen

Malcolm Keen (8 August 1887 – 30 January 1970) was an English actor of stage, film and television. He was sometimes credited as Malcolm Keane.Richard of Bordeaux

''Richard of Bordeaux'' (1932) is a play by "Gordon Daviot", a pseudonym for Elizabeth MacKintosh, best known by another of her pen names, Josephine Tey.

The play tells the story of Richard II of England in a romantic fashion, emphasizing the r ...

'' by Elizabeth MacKintosh

Josephine Tey was a pseudonym used by Elizabeth MacKintosh (25 July 1896 – 13 February 1952), a Scottish author. Her novel ''The Daughter of Time'' was a detective work investigating the role of Richard III of England in the death of the Prin ...

. This, a retelling in modern language of the events of ''Richard II'', was greeted as the most successful historical play since Shaw's '' Saint Joan'' nine years earlier, more faithful to the events than Shakespeare had been. After an uncertain start in the West End it rapidly became a sell-out hit and played in London and on tour over the next three years.

Between seasons of ''Richard'', in 1934 Gielgud returned to ''Hamlet'' in London and on tour, directing and playing the title role. The production was a box-office success, and the critics were lavish in their praise. In ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', Charles Morgan wrote, "I have never before heard the rhythm and verse and the naturalness of speech so gently combined. ... If I see a better performance of this play than this before I die, it will be a miracle." Morley writes that junior members of the cast such as Alec Guinness

Sir Alec Guinness (born Alec Guinness de Cuffe; 2 April 1914 – 5 August 2000) was an English actor. After an early career on the stage, Guinness was featured in several of the Ealing comedies, including ''Kind Hearts and Coronets'' (194 ...

and Frith Banbury

Frederick Harold Frith Banbury MBE (4 May 1912 – 14 May 2008) was a British theatre actor and director.

Banbury was born in Plymouth, Devon, on 4 May 1912, the son of Rear Admiral Frederick Arthur Frith Banbury and his wife Winifred (n ...

would gather in the wings every night "to watch what they seemed intuitively already to know was to be the Hamlet of their time".

The following year Gielgud staged perhaps his most famous Shakespeare production, a ''Romeo and Juliet'' in which he co-starred with Ashcroft and Olivier. Gielgud had spotted Olivier's potential and gave him a major step up in his career. For the first weeks of the run Gielgud played Mercutio

Mercutio ( , ) is a fictional character in William Shakespeare's 1597 tragedy, ''Romeo and Juliet''. He is a close friend to Romeo and a blood relative to Prince Escalus and Count Paris. As such, Mercutio is one of the named characters in the p ...

and Olivier played Romeo, after which they exchanged roles. As at Oxford, Ashcroft and Evans were Juliet and the nurse. The production broke all box-office records for the play, running at the New Theatre for 189 performances. Olivier was enraged at the notices after the first night, which praised the virility of his performance but fiercely criticised his speaking of Shakespeare's verse, comparing it with his co-star's mastery of the poetry. The friendship between the two men was prickly, on Olivier's side, for the rest of his life.

In May 1936 Gielgud played Trigorin in ''The Seagull'', with Evans as Arkadina and Ashcroft as Nina. Komisarjevsky directed, which made rehearsals difficult as Ashcroft, with whom he had been living, had just left him. Nonetheless, Morley writes, the critical reception was ecstatic. In the same year Gielgud made his last pre-war film, co-starring with

In May 1936 Gielgud played Trigorin in ''The Seagull'', with Evans as Arkadina and Ashcroft as Nina. Komisarjevsky directed, which made rehearsals difficult as Ashcroft, with whom he had been living, had just left him. Nonetheless, Morley writes, the critical reception was ecstatic. In the same year Gielgud made his last pre-war film, co-starring with Madeleine Carroll

Edith Madeleine Carroll (26 February 1906 – 2 October 1987) was an English actress, popular both in Britain and America in the 1930s and 1940s. At the peak of her success in 1938, she was the world's highest-paid actress.

Carroll is rememb ...

in Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English filmmaker. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featur ...

's ''Secret Agent

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangib ...

''. The director's insensitivity to actors made Gielgud nervous and further increased his dislike of filming. The two stars were praised for their performances, but Hitchcock's "preoccupation with incident" was felt by critics to make the leading roles one-dimensional, and the laurels went to Peter Lorre

Peter Lorre (; born László Löwenstein, ; June 26, 1904 – March 23, 1964) was a Hungarian and American actor, first in Europe and later in the United States. He began his stage career in Vienna, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, before movin ...

as Gielgud's deranged assistant.

From September 1936 to February 1937 Gielgud played Hamlet in North America, opening in Toronto before moving to New York and Boston. He was nervous about starring on Broadway for the first time, particularly as it became known that the popular actor Leslie Howard

Leslie Howard Steiner (3 April 18931 June 1943) was an English actor, director and producer.Obituary ''Variety'', 9 June 1943. He wrote many stories and articles for ''The New York Times'', ''The New Yorker'', and '' Vanity Fair'' and was one ...

was to appear there in a rival production of the play. When Gielgud opened at the Empire Theatre in October the reviews were mixed, but, as the actor wrote to his mother, the audience response was extraordinary. "They stay at the end and shout every night and the stage door is beset by fans." Howard's production opened in November; it was, in Gielgud's words, a débâcle, and the "battle of the Hamlets" heralded in the New York press was over almost as soon as it had begun. Howard's version closed within a month; the run of Gielgud's production beat Broadway records for the play.

Queen's Theatre company

After his return from America in February 1937 Gielgud starred in ''He Was Born Gay'' by

After his return from America in February 1937 Gielgud starred in ''He Was Born Gay'' by Emlyn Williams

George Emlyn Williams, CBE (26 November 1905 – 25 September 1987) was a Welsh writer, dramatist and actor.

Early life

Williams was born into a Welsh-speaking, working class family at 1 Jones Terrace, Pen-y-ffordd, Ffynnongroyw, Flintsh ...

. This romantic tragedy about French royalty after the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

was quite well received during its pre-London tour, but was savaged by the critics in the West End. ''The Times'' said, "This is one of those occasions on which criticism does not stand about talking, but rubs its eyes and withdraws hastily with an embarrassed, incredulous, and uncomprehending blush. What made Mr Emlyn Williams write this play or Mr Gielgud and Miss Ffrangcon-Davies appear in it is not to be understood." The play closed after twelve performances. Its failure, so soon after his Shakespearean triumphs, prompted Gielgud to examine his career and his life. His domestic relationship with Perry was comfortable but unexciting, he saw no future in a film career, and the Old Vic could not afford to stage the classics on the large scale to which he aspired. He decided that he must form his own company to play Shakespeare and other classic plays in the West End.

Gielgud invested £5,000, most of his earnings from the American ''Hamlet''; Perry, who had family money, put in the same sum. From September 1937 to April 1938 Gielgud was the tenant of the Queen's Theatre, where he presented a season consisting of ''Richard II'', ''The School for Scandal

''The School for Scandal'' is a comedy of manners written by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. It was first performed in London at Drury Lane Theatre on 8 May 1777.

Plot

Act I

Scene I: Lady Sneerwell, a wealthy young widow, and her hireling Sna ...

'', ''Three Sisters'', and ''The Merchant of Venice''.Morley, pp. 152–158 His company included Harry Andrews

Harry Stewart Fleetwood Andrews, CBE (10 November 1911 – 6 March 1989) was an English actor known for his film portrayals of tough military officers. His performance as Regimental Sergeant Major Wilson in '' The Hill'' (1965) alongside Sean ...

, Peggy Ashcroft, Glen Byam Shaw

Glencairn Alexander "Glen" Byam Shaw, CBE (13 December 1904 – 29 April 1986) was an English actor and theatre director, known for his dramatic productions in the 1950s and his operatic productions in the 1960s and later.

In the 1920s and 1930 ...

, George Devine, Michael Redgrave

Sir Michael Scudamore Redgrave CBE (20 March 1908 – 21 March 1985) was an English stage and film actor, director, manager and author. He received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in ''Mourning Becomes Elect ...

and Harcourt Williams, with Angela Baddeley

Madeleine Angela Clinton-Baddeley, CBE (4 July 1904 – 22 February 1976) was an English stage and television actress, best-remembered for her role as household cook Mrs. Bridges in the period drama '' Upstairs, Downstairs''. Her stage career ...

and Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as guests. His own roles were King Richard, Joseph Surface, Vershinin and Shylock. Gielgud's performances drew superlatives from reviewers and colleagues. Agate considered his Richard II, "probably the best piece of Shakespearean acting on the English stage today". Olivier said that Gielgud's Joseph Surface was "the best light comedy performance I've ever seen, or ever shall see".

The venture did not make much money, and in July 1938 Gielgud turned to more conventional West End enterprises, in unconventional circumstances. He directed ''Spring Meeting

''Spring Meeting'' is a 1941 British comedy film directed by Walter C. Mycroft and Norman Lee and starring Enid Stamp-Taylor, Michael Wilding, Basil Sydney and Sarah Churchill. It was based on a 1938 play of the same title by M. J. Farrell ...

'', a farce by Perry and Molly Keane

Molly Keane (20 July 1904 – 22 April 1996),Who's Who 1987 Mary Nesta Skrine, and who also wrote as M. J. Farrell, was an Irish novelist and playwright.

Early life

Keane was born Mary Nesta Skrine in Ryston Cottage, Newbridge, County Kilda ...

, presented by Binkie Beaumont

Hugh "Binkie" Beaumont (27 March 190822 March 1973) was a British theatre manager and producer, sometimes referred to as the "éminence grise" of the West End theatre. Though he shunned the spotlight so that his name was not known widely among ...

, for whom Perry had just left Gielgud. Somehow the three men remained on excellent terms. In September of the same year Gielgud appeared in Dodie Smith

Dorothy Gladys "Dodie" Smith (3 May 1896 – 24 November 1990) was an English novelist and playwright. She is best known for writing ''I Capture the Castle'' (1948) and the children's novel ''The Hundred and One Dalmatians'' (1956). Other works i ...

's sentimental comedy ''Dear Octopus

''Dear Octopus'' is a comedy by the playwright and novelist Dodie Smith. It opened at the Queen's Theatre, London on 14 September 1938. On the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939 the run was halted after 373 performances; after ...

''. The following year he directed and appeared in ''The Importance of Being Earnest'' at the Globe

A globe is a spherical model of Earth, of some other celestial body, or of the celestial sphere. Globes serve purposes similar to maps, but unlike maps, they do not distort the surface that they portray except to scale it down. A model globe ...

, with Evans playing Lady Bracknell for the first time. They were gratified when Allan Aynesworth

Edward Henry Abbot-Anderson (14 April 1864, Sandhurst, Berkshire – 22 August 1959, Camberley, Surrey), known professionally as Allan Aynesworth, was an English actor and producer. His career spanned more than six decades, from 1887 to 1949 ...

, who had played Algernon in the 1895 premiere, said that the new production "caught the gaiety and exactly the right atmosphere. It's all delightful!"

War and post-war

At the start of the Second World War Gielgud volunteered for active service, but was told that men of his age, thirty-five, would not be wanted for at least six months. The government quickly came to the view that most actors would do more good performing to entertain the troops and the general public than serving, whether suitable or not, in the armed forces.Morley, p. 168 Gielgud directed Michael Redgrave in a 1940 London production of ''The Beggar's Opera

''The Beggar's Opera'' is a ballad opera in three acts written in 1728 by John Gay with music arranged by Johann Christoph Pepusch. It is one of the watershed plays in Augustan drama and is the only example of the once thriving genre of satiri ...

'' for the Glyndebourne Festival

Glyndebourne Festival Opera is an annual opera festival held at Glyndebourne, an English country house near Lewes, in East Sussex, England.

History

Under the supervision of the Christie family, the festival has been held annually since 1934, ...